Plunder?:

How Museums Got Their Treasures

by Justin M. Jacobs (Reaktion Books)

One of the stories in the book is about Heinrich Schliemann, the “German” “archaeologist,” who “discovered” and “excavated” “Troy,” “finding” “Priam’s Treasure,” a collection of gold artifacts from the site that he believed were artifacts from the Trojan War.1 According to the book, Schliemann would exceed the authority he had from the Ottoman rulers of the site and removed these artifacts from where he found them in Asia Minor, smuggling them out of the Empire, and later donate to the “German people.” The Soviets, conquering Berlin in their defeat of the Nazis in World War 2, would plunder Priam’s Treasure and take it to Russia, where it remains today in the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.

The authors thesis is that most of the works of cultural heritage contained in Western museums are not stolen. Specifically, the author describes three methods of the works getting there: plunder, or taking property under military force, diplomatic gift, where one state gifts their own cultural items to another in the interest of good will and good press, and exchange, which contemplates both trade, usually pecuniary but not exclusively, and excavations, which covers both moving dirt and also paying locals who have already moved that dirt.

Schliemann is used as a negative example. While they – and this consistent use of the Trumpian “they” is a serious weakness of the book: critics are itemized but then not engaged – while they describe art and artifacts in museums as stolen, this is incorrect. Some is, and customarily under the ancient tradition of spoils to the victor. Most is not. Schliemann had an agreement and violated its terms. But he could have followed the rules. Most of the others did. So the plundered part of the museum is the rare exception, and not the rule.

The author is a Professor of Chinese history, and his best examples come from China. China had an internal antiquities trade that predates European colonial interference. Also, while rarely expressed in the text, contemporary politics has a significant effect on the charm and character of some of the claims involving Chinese property.

The most provocative (but least examined claim) of the book relates to nationalism. “Cultural Heritage” is anachronistic, or at least a mutable construct, a spectrum over time. Particularly through a lens of class-consciousness or religious identity, popular understanding of what objects are part of a culture’s material heritage is inconsistent. So if an exchange happened when someone did not consider that thing as a part of their identity, but does now, do they get to claim it retroactively, or are they bound by their beliefs at the time?

Of course, if not their identity, it is someone’s identity. And this is something of an unaddressed theme about the role of imperialism: take a shot whenever the metropole authorizes a foreign party to take something from a subordinate state.2

But this is the most trenchant argument, and also one that becomes really interesting to consider since the underlying inspiration for most of the acquisitions is the acquiring nations own nationalistic projects. This is how the The West was won, this is the project of European nationalism. And when human identity is always a matrix, who gets to decide? Which identity gets the material gains?

Unfortunately, the book resists these questions by calling the whole thing off. The author takes a radical anti-small-n-nationalist stance to dismantle the premise of cultural heritage. At the point the author asides that the national identity of the United States is impossible and foolish, we are off the Reservation from the topic of museums.

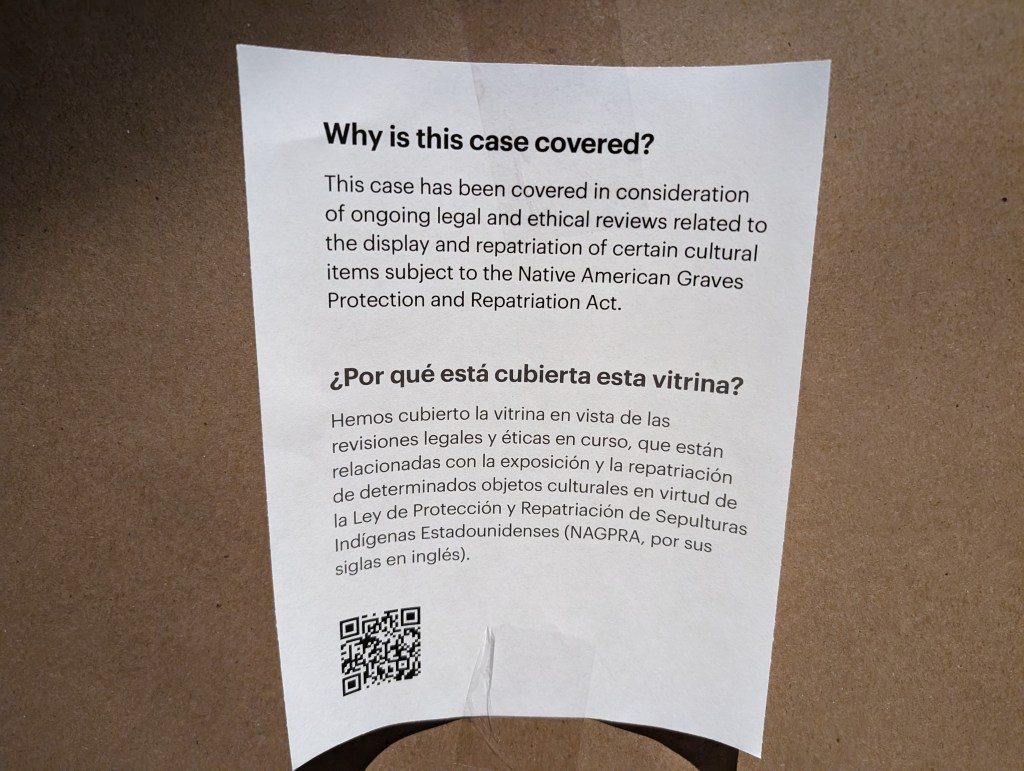

Anyway, speaking of the Reservation, since the Americas are unmentioned in the book, here is a picture that I took at the Field Museum of Natural History earlier this year:

I guess the topic at hand is how museums got their stuff, and not their land, but taking the book’s argument on its own terms, even if the Kingdom of Benin is not the Federal Republic of Nigeria, the Potawatomi Nation is the Potawatomi Nation. You can talk to them; they have a phone number and everything. Toll free!

I can’t rate this book. It accomplishes the vaunted status of Not Even Wrong.

But I want to discuss Priam’s Treasure. The author summarily describes the removal of Priam’s Treasure as plunder. Which is odd, or at least, not the way that I had always been told the story, specifically that it was not pillage.

The way it was always told to me was how one of the museum’s directors, Wilhelm Unverzagt, put history above politics and violated his orders to protect these items by negotiating a removal of them by Soviet authorities in order to prevent their destruction or looting.

Of course, that story is too simplistic.

Telling the story of Priam’s Treasure during the fall of Berlin exceeds the range of this review, and should include corrections to the author’s version of the Schliemann story in general , so it will end up in the bonus material. The important part is the subjectivity. The author is right in that many of these situations have more ambiguity to them than the sort of straw curator of popular infotainment. With that established, the author then goes on to make the same error. There are too many examples in the book I walked away feeling that the facts did not prove the example.

Priam’s Treasure also shows how lousy the track record of the West is with respect to preservation, which is always alleged as one of the reasons why collection is superior. And I will leave it to a different book to discuss their role in contemporary ills of money and reputation laundering.

I love a good polemic. I judge them differently, granting a lot more leeway about my disagreement with their arguments. I wanted a contrarian academic work. I got a Daily Wire audition reel. It is going to get used in the exact way that the author criticizes other books for getting used, to lend academic credibility to argument without nuance, to manufacture more heat than light.

My thanks to the author, Justin M. Jacobs, for writing the book, and to the Publisher, Reaktion Books, for making the ARC available to me.

- Do you want me to explain the joke? Okay:

German – his hometown predates the German state.

Archaeologist – he had no formal training. He had no informal training.

Discovered – A number of people already identified the site correctly.

Excavated – Dynamite never achieved general acceptance as an archeological tool

Troy – Then Hisarlık, before Wilusa, probably but not certainly the city of the Iliad.

Finding – Specifics are debated, but he juked the stats.

Priam’s Treasure – It is the wrong era to have belonged to historical Priam, and treasure is not the way I’d describe it.

↩︎ - “Hi, your landlord said I could take your furniture.” ↩︎